27-pictures challenge

[2 days since I finished working]

[5 days before coming to Canada]

There is this exercise that I saw from the Human-Centered Design toolkit: One disposable camera is given to a villager, who then self-document his life. The idea is that pictures don’t lie, and that it gives a better description of the person’s livelihood than a plain interview. It’s also that pictures focus on what people have and value, and not on their perceived problems.

I thought that I could also use it to show what working in Ghana was like for the past 3 months.

So this is the 27-pictures Challenge:

– Find one photo corresponding to each of the following categories

– Use a maximum of 27 words to describe.

1-4: pictures of me

5: my pocket/purse

6: what i wear on my feet

7: where i live

8: where i work

9: where i sleep

10: what i see when i step outside

11: where i shop

12: what i bought for 1 cedi

13: my favorite drink (star)

14: my favorite food

15: you can only find this in ghana

16: i wish i had this

17: i spend most of my time here

18: something i need

19: someone i love

20: where i relax

21: where i spend time with friends

22: someone i respect

23: beautiful to me

24: something i worry about

25: something i am proud of

26: something i want to improve

27: i use this every day

Enjoy.

I hope it gave you a better image of what my 3-month placement was looking like 🙂

For other JFs out there: I challenge you to do the same with the thousands photos you took!

Julien

Where spontaneity and curiosity brought me.

[5 workdays left]

“50km from Wenchi is Hani, one of the best-documented archaeological sites in Ghana. ” – That’s pretty much the only information I had before going there. I copied the maps of how to go there, then went to the Tro station.

With the little twi I have, I ask a taxi driver how much it costs to go to Hani. He says 1.5 cedi, which seems normal for a shared taxi, so I don’t negociate. There’s another woman already waiting to go there, so I hop in. I’m surprised that we leave with the taxi half-full. He must be impatient to go, I think.

A funny fact about Ghana’s currency is that 3 years ago, they chopped 4 zeros, but people are still used to the old currency. So when one say 15, he means 15 000, which now is worth 1.5. Well, in this case…15 cedis meant 15 cedis.

So I find myself in the middle of nowhere (Hani), no network, shouting at the taxi driver and trying to bring the price closer to 1.5 cedi. I didn’t bring that much money, so I am scared not to make it home. One man named Oscar comes during the argument and ask if I am Richard’s brother. I frown. It happens that there’s an american peace corps based in Hinu, and that since I’m another white man, I must be his relative. I end up paying 10 cedis to the pissed driver, and follow Oscar.

– Kofi Richard! all the kids think I’m the american.

– No, my name is Kweku Julien.

– Oh…Kweku Richard!

We never find the man. So, we direcly go the group of elders, as must any visitor. 30 minutes of greetings and one full glass of gin later, we then walk to the chief. A man wrapped in tradionnal cloth is surrounded by 5 men. They discuss very seriously for 10 minutes. Then, Oscar translates:

– You must pay 10 cedis for a chicken to be killed tonight. You must also buy a bottle of alcohol.

That’s Ghana’s version of entrance fees, I guess. One other full glass of gin later, I go buy a bottle for 4 cedis, than one elder named Abraham brings me to the site.

So you know the cliché image in movies where one black man clears the way in the jungle with a machete to a white man walking behind traying the fight the weed and the branches? Well, that was us.

Abraham brings me in the middle of a weed field. Not far, I see the mountains seperating Ghana from Cote d’Ivoire. He shows me a small cavern in the ground leading to two holes. The legend says that from one came the Akan people, and the other the Muslims. The Muslim fled to the north, while the Akan stayed for 40 days. The whole is supposed to be protected with a concrete door to protect from erosion. But they fear that by putting the concrete on, the spirits won’t be able to go free and will feel imprisonned inside, so they never put it on. Abraham fills a glass of gin, gives his greetings, and then throw it in the hole. We also drink the same amount each.

He then leads me a natural borewhole, where the people were drinking water. We then walk away to the forest side.

He brings me to an open area. The soil is hard rock, and there’s about 40 holes in the ground. Apparently, that’s where some people, who were there long time before year 1, used to grind millet. He shows me one of the stone, who was used to crush the cereal to flour. Apparently, they found lots of tools and crafts here originally, but they were taken to one museum in Sunyani. It was cool to walk where some humans walked ages ago, when the world population was probably less than a hundred thousands.

On the way back, I did a little bit of work: I started asking about Record keeping and business planning to Abraham, who was a cashew farmer himself. I probably asked him hundred questions…At one point he even said, “if you ask me all these questions, it means you know something I should know!”, and I started giving him a short version of my course!

In the end, I never met that Richard. And the rest of the gin went for the chief of the village, of course.

Coming back to Wenchi was a much easier task. A taxi brought me to Namase for around 1 cedi. Then I took one directly to Wenchi, as the sun was getting down.

I arrived on time for the fufu.

Post-Prototype

[1 week since Prototype]

[7 workdays left]

Mr. Nsiah Robert is one of the five farmers who came for the course. There is something about the way he walks with determination, sits with the back straight, and listens to you with open ears and a small smile, and speaks with a calm voice…he inspires wisdom.

I interviewed Nsiah before and after the course, so that I can get an idea if the course is effective at changing behaviours. I even used a qualitative scale of four stages for the several points I was looking for. Stage 4 being the ideal, Stage 1 being “I don’t notice anything”.

Note: this is not supposed to be scientific at all. It’s just to give an idea.

So Mr. Nsiah was not strange to Business skills before coming to the course. He was already selling in group, had small records, and had a good understanding of loans. He’s someone you can call an early adopter: he’s easily convinced to try new technologies. The proof of that is that the same farmer attended a demonstration on why cowpeas are beneficial to your lands; the same day, he decided to go with cowpeas for the next season.

I asked him questions about what he remembered from the course. I also presented him scenarios to test out his business skills: What if a person comes to you with a better fertilizer, but that costs double? What if there’s someone who wants to buy your tomatoes at a good price, but is 10 miles away, and doesn’t offer transport?

Already, I felt that big chunks of the message got washed away, but small pearls remain. It seems the biggest changes were in record keeping: he went from taking few records to understanding how to use them for his planning. He also adopted the idea of making cost/benefit analysis for choosing most profitable venues. Finally, he understood that taking a loan requires a plan on how to pay back the money on time. So you could say the course was effective for him.

I asked him: he were to do the course again, how much would he be ready to pay? The answer was astonishing: 100 cedis! It’s interesting, because when I ask extension agents what was the main reason they were not able to recruit more, they said that Price was the number one reason (followed by the No transportation included, then No food included). If I understand well, there’s a small category of farmers who are ready to pay. These farmers have attended workshops in the past, and therefore value education. They are early adopters, therefore value any information that will improve his farm.

More generaly, it seems that there’s only a pocket of farmers who would attend the course, even if it was free. I think it’s the word “classroom” that would scare most of them away. Not understanding that the class is adapted to everyone, they would not believe that they would understand much. But we also can’t ingore the extension agents’ perception of their farmer : if they doesn’t believe in their farmer’s capabilities, they won’t invite them.

I have a mix vibe about the course being an effective solution. On one side, I can see 40 farmers being trained every year, and coming out with the right attitude. On the other hand, I’m thinking of all the small-scale farmers who, for various reasons, won’t attend the training program. And they’re the people that EWB is supposed to work for…So it’s a good course, but not an elegant solution.

Still, a lot of valuable lessons already emerged from prototyping the course: We got to test the farmers willingness to pay; we got to understand the limitations of extension through a centralized education model; plus we setted up good relations with the Farm Institutes, and understood how to work with them.

For the sake of making this post short, I’ve really condensed my observations. But if there’s anything you’re interested to know about the course and its results, please ask! 🙂

Julien

Prototype time

[1 day since end of Protype]

[10 workdays to go]

[4 weeks till you see my face again]

Yesterday, around this time, I was handling certificates to the first batch of farmers taking the Agribusiness Training Program.

Overall, I think the course went well. I really believe that the participants went home with more than a paper. Some realized that if they were to take record keeping more seriously, they could more easily identify their mistakes and progress every year. Some others understood that if they were to follow a budget and save small, they will be less likely to fall short before the end of season and have their farm under-financed.

During the three workshops, I did not do anything. I didn’t teach, I didn’t speak, I didn’t contribute. The only thing I did was buying water bottles, and printing certificates. But why? You see, the goal of the prototype was not to make everything right, it was to see what is presently wrong. Once I will be gone, the Farm Institute will (hopefully) continue to teach the course. So I had to make sure that the documents we prepared were self-sufficient.

We spotted a lot of mistakes. Some discussions questions did not lead to anything usefull. Some activities did not achieve the expected results in the students. But I still feel that overall, the message got through.

I was also looking for answers to three big themes: Feasibility, Usefullness and Effectiveness.

Is the course feasible?

I can see the course being taught again and again. The only issue is that not all farmers can aford the fuel or the taxi money to come to the Farm Institute. So the course can only be taught to more “well off” farmers. The farmers who came were not subsistance farmers: they had many acres of land and were employing many men. But in a sense, I believe that it’s them who should benefit most from the course: now that they have probably the good techniques for their farming, they can concentrate on the business aspect. In a way, the course is building the capacity of hardworking farmers, who will then be able to employ more employees.

Was the course material usefull?

Overall, most of the activities seemed to be usefull to support the teaching. I might not be objective here, but I think that the course that went the most well were the ones where Bright stickly followed the course material: the thoughts were more structured, the message was clearer, the time was respected.

Is the course effective for teaching agribusiness to farmers?

I think that the course was effective at highlighting the importance of business skills, but not necessarely at showing them. It’s one thing to speak about the importance of record keeping, but it’s another to actually assist the students and show methods on how to take records. So I added some “practical tips for participants” to the tutor booklet, hoping that it will be better next time.

One other question I wanted to test out is:

Are farmers willing to pay for agribusiness education?

On the first day, the farmers handed the 15 cedis without arguing. I expected to have to justify the cost and do some negotiation, but no. The money was for bottled water, snacks, malt, certificates, notebooks. I think it had an effect on the farmers chosen: they were all producing 8 acres or more of cashew, in addition of all the other crops. In a sense, they were not subsistence farmer – yes they lack business skills, but their business is rolling nonethess, and employ multiple workers. One was national best farmer or something two years ago, and another came second place. The question is, is it really that only this type of “advanced” farmer is willing to pay, or is it the AEAs who suggested them who thought only they would be willing to pay? For that, I have no answers. Another point is that when I asked tutors if we should charge next time, all said no, despite the fact that there was no problems encountered with the paying…Apparently, the problem is that when you invite people (even by advertisement), they shouldn’t be paying, which is different from if they come by themselves…

One big challenge during the prototype was the language barrier: all the course was given in twi. Fortunatly, ghaneans use a lot of English words, so I was able to know what they talked about. Though, I had to interview the tutors present at the course afterwards to fully understand what was discussed.

For the rest of my stay in Ghana, I will be meeting with Margaret, who will replace my partner Bright in farm management. She will be taking responsability for the whole course. So we will have to go over the whole program, practice the activities and make sure she takes ownership of the whole course.

By the way, sorry for the lack of pictures; I either lost my camera, or got it stolen

Julien

What Ghana taught me

I was supposed to post this yesterday, but the connection was not working well.

[2 days since start of Prototype]

[about 2.5 months since arrival]

First day of the Agribusiness Training program: check.

Last tuesday, 5 farmers came to the farm institute for their first lesson, which was a general introduction. Before going further, we wanted so see what kind of farmers we had. It happened that for all of them, cashew was their main source of revenue. So Bright decided to ignore the other crops for the course, so that we primarly focus on the business skills, and not each crops’ technicalities.

He started by asking them about their past season: how much did they produce? What challenge did they face? By writing their stats on the board, we saw that some farmers had better performance than others. But all were only producing 2 or 3 bags of nuts per acre – whereas the average should be 10-15! This lead to a fruitful discussion of what they could do to perform better, and where business skills would fit in all this.

I think it’s too soon to say if the course is a success or a failure. So I’ll pause that for now, and give you more insights in a week!

—

In few days, I’ll have been in Ghana for 3 months. And I think I’ve grown a lot since then! Starting from less serious to more serious, here’s the four things I’ve learned since I came here, and that I will bring back to Canada:

1. Washing by hand

Every week, I need to wash all my clothes by hands. And there’s a lot to wash! There’s the sweat from me biking home during the hot peak. There’s the dirt coming from the unpaved roads, or the visits to the farms. And there’s the food spillovers, from not knowing how to eat with my hand.

Now, I’d say I’m as fast as a washing mashine, using half the soap and water, and probably twice more efficient. Here, I’ve removed stains that were on my clothes for a year! Be sure that if I get a wine stain in Canada, I’ll get the buckets, the soap, and use my man power.

2. The importance of images

Ghanean LOVE images. Give a normal speach in a meeting, and you’re likely to get one person asleep, and two others not paying attention; but then convey the same message through a story or an allegory, and they will be listening to you. Even more, you will see them repeating the story to others!

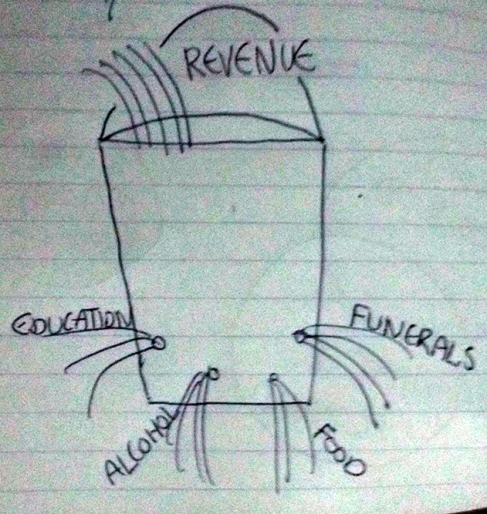

For example, we starting talking about proper finance in the course. So we explain the image of the leaky bucket (which is NOT from me, by the way): a Farm is like a bucket with holes at the bottom. The water you pour at the top is your revenue. Each of the whole are your finance leaks. The goal of proper finance is saying: which holes should I fix? And I think it conveyed the message perfectly.

I think that even in Canada, I’ll spend an extra time thinking about presentation: it’s so much more interesting to read a 10 page documents when it’s full of anecdotes than plain theory!

3. Don’t stick to the plan

I find that in Canada, we looooove to make plans. We have our schedules for the week, our deadlines when doing group work, our general objectives for the year. And so when the reality doesn’t follow the plan, we try to change the reality so that it fits our expectations. So plans have precedence over reality…

In Ghana, let’s just say things are doomed not to happen the way you thought! For example, the course didn’t go as expected. People got an hour late, yet I was stress-free. We could do a part on Proper Measurements, but the students were too experienced to need it. But then a lot of good points that were not planned came up, and so the first class was a success.

I think I will use planning more as a preparation tool than building a hard-steel schedule, and trying to fight reality.

4. Work with what you have

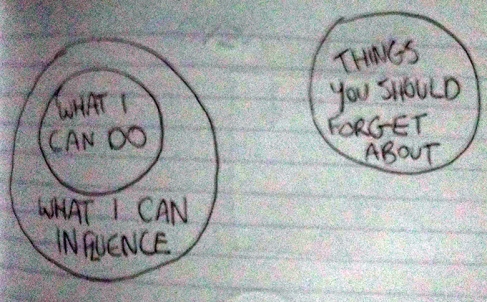

I explained the metaphor in a previous post. The idea is that there’s three zones in which you can work:

-the Green zone of the things you can do,

-the Yellow zone of things you can influence,

– and the Red zone of the things you can’t either do or influence.

It’s something that I had to explain really clearly when I came in: No, I’m not here to bring fundings or tractors. And there’s a limit to what I can advise to the head office at the end of my placement. Thought what I can do is improve the shool’s agribusiness curriculum.

If you don’t pay attention, it’s really easy to slip into Red zone: you end up complaining about nothing works, and stay paralysed. Shifting into yellow and green is much more productive, and very much less cynical.

I think my vision of the world and of development has changed over the past month. But that will be discussed in another post!

If there is any JFs reading this blogpost, I’d be VERY interested in knowing what YOU have learned so far. Please leave that in the comment section 🙂

– Julien

The dam in the way

[19 workdays left]

[2 days before prototype]

Bui National Park is located along the Ivory Coast border, in both Tamale/Brong-Ahafo region. Surrounded by moutains born from nowhere, crossed by the Volta River, its forest is home to 3 types of monkees, while its watersides welcome 200 hyppos, the largest family in West Africa. Or at least, that’s what the guide said.

The reserve is at 1.5 hours from Wenchi. Out of all the JFs, I am the closest to the park, so I thought it would be a shame not to go. I was attracted by seing the hippos, but also heard about a hydropower dam being built there, and was interested in seing it.

Okay, maybe you guessed already, but I didn’t see any hippos. Nor any cool animals (that excludes goats and chickens that I see everywhere). And it did rain most of the time. But somehow, it was a very good weekend. I guess it was about being away from anything known that was thrilling.

When I got on the tro going to Bui, two girls from Europe were already sitting there. Irish from Holland and Thea from Norway. We bounded quickly, at first by necessity – we were the only tourists going there, and share the same bungalow.

In the evening, a guide walked us to the Volta Black River. On the way, we saw this huge pile of rocks between two mountains: they were basically closing the little gaps between mountains to make the dam basin. That’s when I realised that where I was stepping was to be 30 feet deep in a year.

Bui city was originally located along the river side. Though, the dam workers deported the people 2 kilometers away inside the lands, and built the villagers new houses. Now most people in Bui make a living out of fishing in the river, so they walk everymorning to their old town, back to their boats. The canoes rest by the od houses ruins, and beside underwater mango trees. The hippos were originally there, but recently, they have retreated where the water was less shallow. It felt like we’ve missed the boat.

All the New Bui houses are made of Wood, which is really weird in Ghana. I learned that it’s the Russians that built those with their own wood, when they started the Dam project few years ago. Now, the contract is given to China.

Just before the night, we climbed this mountain to watch the sun die behind the mountains. There we were, Ghana on one side, Ivory Coast on the other, fumes coming out of the three neighboring countries, and the endless forests. For a second, it felt like we were on top of the world, or that the world was swallowing me.

On the next day, we unsucessfully chassed monkeys. We walked in weed as tall as us, and we couldn’t see anything. The guide said that the monkeys didn’t like tall grass. He asked us to come back in the dry season.

On the afternoon, I came back to the Sunset mountain, with no guides, nor europeans. Just me. I had a nice meeting with myself: I reflected on my career plan, my personal life, what I should learn from the past, and what I should expet from the future. It’s all things I thought about since coming here, but there, everything seemed more clear.

When I came back, we visited the Dam itself. It was huge! Some part of the contract was given to China: most of the supervisors were chinese, while most workers where ghaneans. In a way, I’m glad that it was built there: there’s only 3 missfortuned villages around it, and no cultural landmarks to be flooded. The dam will probably help Ghana’s intermitent power shortage, and even serve as a good export product. Yet, I’m annoyed to see that it already disturbs the largest hippo population in west africa.

Me and the girls, we ended getting along very well. We spent the nights discussing about the differences and similiarities between our 3 countries. Education, funerals, religion, loans and cost of living, politics, going out habits, languages and dialects…and life in general. We took the tro back to Wenchi, then they went back to the orphenage where they were working, and me to my

Now, there’s 19 workdays left to my placement. And it seems so short for all the things I want to do! Yes, the course is written, but if I stop now, it will remain on a shelf gattering dust. So the hardest part starts now.

In transit

This post is not about Wenchi,

it’s not even about Bosumtwi lake, where I spent the weekend

But about what happened in between.

Tro-tro: noun. name given to each of those vans. They were probably designed to get 8 people; here, they were revamped to welcome 15. At the Wenchi Tro station, there’s about 50 of them, all going in different directions. Together, they make up the transportation system of Ghana.

I go to the boot, and say “Kumasi”. 5.50 cedis, tells me the ticket seller. That’s about 3$ for a 4 hour ride. I take place in the tro. If I’m lucky, I’m the last one, and the ride is ready to go. But today, the last tro left in front of my face; and so I’ll probably have an hour to wait inside the car.

Sellers go around the tros, selling everything from water sachets to ice cream to books to fried-something to hankerchiefs. One guy shows me “Animal Farm”, printed on kraft paper. He starts at 15 cedis, but I get the price down at 5.

The ticket seller pays the driver’s share, then he starts the engine. Everything is privatly owned: corporates own the tro-station, than all the drivers own their cars.

There’s a general statement that the Ghanaean transportation is inefficient. Of course, when saying this, we mean “less efficient than the ones in our canadian cities”. I have my doubts. For that if we define efficiency as price per kilometers or hours, here it’s still good. Even the fuel efficiency must be better, for that a tro never leaves until it’s full. But when we say efficiency, we usually mean the time to travel a certain distance, and for that, I must admit it’s pretty bad.

Now must people don’t have cars here. The few exceptions I’ve seen were government workers: the headmaster of the FI, the accountant and one tutor. I’ve seen a lot owning a moto, and some having bicycles. But most people only own their feet, and therefore rely on the tro-tro system and taxis for long distances.

Taxi: noun. a normal car, but with yellow stickers at each corners. Garnished with certification stickers from 2010. Fueled by propane, probably because it takes longer for a tank to get empty.

Taxis are used in between closed cities or neighbourhoods. Going alone will cost you 5 to 8 cedis, depending on distance. Sharing on others can drop the price to 0.30 cedis. Sometimes, I see woman from villages coming in taxis, with their load of cassava. There’s something strange in the image of a rural farmer calling a taxi to sell his crops.

On the tros and taxis, you really get a long time to think – a lot. Like: would this whole system be better if it was nationalised? What if suddenly all tros were suddenly in the hands of government, and that all drivers became government employees?

I think it wouldn’t make a difference. I think the problem lies somewhere else.

What makes Montreal’s transportation system so good is that they work according to statistics. Buses leave the stations half-empty, but that’s because it has been calculated that on average, they should a pretty good number of people picked up along the road. If the bus pass every hour, at least the person knows when to leave his house, and therefore loose less time waiting.

On the other side of the sea, people can wait an hour for the tro to finally leave. And on the road, if there’s anybody going in the same direction, he can’t hop, because the ride is full. So the person has to take a private taxi to the nearest city, making transportation expensive for people outside of big centers.

I can’t seem to see how this system would evolve in something more efficient. I’ve thought about it many times, on any of the travel I’ve taken, and yet couldn’t come to an elegant answer.

If you can’t change the tro, you can still change the road.

Here, there’s a competition on which road is worst. Take a map, and find the three following cities: Damongo, Tamale and Bolgatanga – hint: it’s in the northern part. The distance from Tamale to Damongo and Bolga are 4 hours and 1 hour. Yet, Bolga is probably twice a far as Damongo from Tamale. Why? The answer is that the road to Bolga is a nice, smooth path; whereas for Damongo, let’s just say sleeping on the tro is impossible.

So sure, it takes me more time to get everywhere. But there’s much more worst effects from having an overall inefficient transportation system: isolation. The general idea is that if villages are isolated, and if people from these villages have no good ways of getting to the urban centers, well they are isolated socially and economically. Having bad rural infrastructures not only slows down people, it slows down market access, health services and appropriate technologies dissemination.

Hear me well, the solution to poverty is not building better roads, and getting better transportation systems; thought it is probably one of the ingredients. Even if you were to build highways in between villages, there would still be systemic reasons why development wouldn’t go at 100 km/h.

Alright, I’m now arrived in Bosumtwi Lake – Wikisearch it, it has an interesting story.

Enjoy the scenery.

(As Always, I’m curious to hear your thoughts on all this – Julien)

First milestone

[11 days before the course start]

[say…6 weeks before I return home]

Hey Internet,

This blogpost is about what I’ve done so far, and the lessons I’ve learned on the road.

So the write-up of the business course is finally done! And I’m pretty proud of how it looks. It’s really not the typical “writing on the board” type of courses. To suit the illiterate audience, it combines discussion questions, practical activities and assessments. The course is not about teaching advanced accounting or entrepreneurial theories: it’s basically a nice way to say to farmers “hey, you gain a lot by writing down your expanses, thinking ahead and making profit-based decisions”.

One challenge in the writing was about the size of the class: is it normally going to be taught to one farmer, or to 50 of them? I decided to go with the first option. Therefore the lessons are highly centered on what the students have been doing before the course, and what is the way to improve it. The problem is that this type of approach is impossible with 50 students: the course is bound to be taught to small groups.

Talking with a lot of people made me realize that the “one class everyday for 2 weeks” format was not realistic. Farmers can’t afford the fuel to move everyday to the Farm Institute and come back, nor can’t they afford a missed day of work, during harvest time. So we switched to 4 workshops a week, devided in two days: Tuesdays and Fridays. Depending on communities, these are the two taboo days for farming.

I’ve uploaded on this googledoc, so that you can look at it. The page setup was a little messed up along the way, so sorry for that. I am yet to do a grammar check of the whole document. For that, I’ve divided the document in pieces, and 10 volunteers JFs kindly accepted to go over the English mistakes!

The marketing of the course is also a struggle: I am I supposed to find 5 farmers who would want to pay 15 cedis for the course? I can’t ride a motobike and ask every one on the road. So I’ve called a meeting with 5 extension agents: they are in charge of around 2500 farmers, so they are better positionned to advertise the course.

I was really worried about the incentives: why would an extension agent promote a course for me?

– First, I’ve setted this nicely: this agribusiness course was complementing their own work, and they would see improvements in their own farmers.

– Second, I’ve asked them to “nominate” one farmer: it’s a suttle difference, but it probably made them thinking “Right, I have to find one farmer” instead of “I have to promote the course”.

– Third, I’ve noticed that some extension agents wanted to participate in the course as well. So I’ve set it clear: only AEAs who find a farmer can come to the course as well. They laughed, and agreed.

So was it successfull? So far, I have 4 names and phone numbers noted. And at least 3 more are coming. Will the participants actually show up on the first day? That’s another question!

11 days before it starts, and there’s still so much to do!

– Find a cattering service. When Ghaneans come to a workshop, the least they expect is free food. So finding affordable lunches is crucial, if we want them to come back on the next day!

– Advise the other tutors. So far, me and my partner Bright have been working on this in the dark. In a meeting next week, we will reveal what we have came up with and how they can contribute during the prototype.

– Invite a Susu Collector. In Ghana, there are these banking cooperatives called Susu. They go to farmers and collect small money, and give it back in when he needs it without conditions. I thought that they were better positioned to talk about saving to the student, so I invited a Susu collector to come. Hopefully, it will shift the mindset from “I want a loan” to “I need to save”. It was not hard convincing one to come during the course. The next step is making sure that they will convey the right message.

In two weeks, I should be able to answer the following questions:

– Are farmers really willing to pay 15 cedis for an Agribusiness course? If yes, what type of farmers are they?

– What is the way forward for the course? Is the centralized approach (making farmers coming to the FI instead of going to them) the right way? How can we make sure the FI will continue doing the course after I’m gone?

If you have any questions or comments, again, I’ll answer them 🙂

– Julien

Vision 2020 for Agriculture in Ghana Pt. 1

Vision 2020 for Agriculture in Ghana.

[15 days until prototype of course]

My friend Guillaume did recently this series of blogposts on his challenges in Ghana, This inspired me to do the same with Agriculture. And I’m kinda stealing the title from Ryan’s post.

Part 1: For a stronger role of the private sector in providing extensions services to farmer in Ghana.

– Okay, that’s a long title, but I couldn’t find shorter, and less serious. So let me explain:

Extension services refers to any kind of information about best-practices provided to farmers. Answers to questions like, How should farmers plant their maize? What is the ideal distance between cashew trees? Why is my plantain trees covered with white spots? People who provide those answers are called Agricultural Extensions Agents (AEAs). Like engineers make the bridge between science and humanity, AEAs extend the research institutes’ knowledge to farmers.

In the present system, AEAs work for the government, under the Ministry of Food and Agriculture. This leads to the following issues:

– AEAs are underfinanced. Less then 10% of government’s budget goes to agriculture. So they are asked to change the world, but given very limited ressources. Since couple of months, due to a inflation crisis, they have not received any money for their fuel, so they are basically volunteering right now.

– Not enough AEAs. Extension agents are usually responsible of 2000-3000 farmers. For a 40 hours week, that’s about a minute given per farmer.

– AEAs wear multiple hats at the same time. In Canada, they would have all the following titles: land surveyers, agroeconomists, agriculturalists, business advisors, teachers, etc. They are asked to be experts in every crops, animals and processing methods.

– They work by area. The underlying assumption is that all people in the same place require the same information services, which is untrue. They are asked to answer thousands of different questions every week, making the whole process of information transfer inefficient.

– Decisions are centralized. Let’s say an extension agent found a really good way to teach agribusiness to farmers. Even if the results were delivered, at the end of year, it’s the government who decides in which programs to put the money. And so any novelty born at the bottom is killed by the policies at the top. This is what happened to the Agriculture As Business program.

For these reasons, I call for a stronger private sector in extension services for 2020. In clear, that would mean that the private extension agents (PEAs) would be paid by the customers. What would it look like? Farmers could pay each time they receive a service, say 5 cedis to get your land measured and mapped. Or they could pay every year, say 1 cedi to get supports for Cashew trees.

– Logically, they would serve just the right amount of farmers. Less people would diminish their revenues, and more people would harm the quality of their service.

– PEAs would only wear one hat, say Fertilizer expert. Farmers would have their set of PEAs corresponding to their needs.

– They would work under competence, not area. Each PEA would therefore become real experts in their respective fields.

– Free-market principles would make the whole thing dynamic. PEAs would contantly have to adapt their methods, if they don’t want to be outcast by competition.

In my view, this would result in better services provided to farmers, therefore a stronger agricultural sector for Ghana. But there’s always the risk that the poorest of the poorest, who would need the information most, couldn’t aford the services. Or that some necessary areas of extension services would not be profitable for private companies, are therefore be left out.

So why isn’t it happening? My team leader Erin, got the answer. She presented the idea of paying for information to a rural farmer, and started at 1$/year, hoping to increase the price and see how much would a farmer pay. But immediatly, the guy replied no: why paying for something that they already can have for free?

What’s preventing a market from emerging is purely the farmer’s perception. First, we have to convince farmers that paying themselves would result in better quality services. But Extension Agents have already struggles convincing them that planting in rows is more efficient in the end. The idea is miles from them.

I’m lying.

There’s already one example of private extension agents: veterinarians. Even thought AEAs also wear that hat, most people are ready to pay for a rapid, efficient check-up. My hypothesis is that lifestock and poultry farmers have a better business mindset, and that therefore see the use.

Another great example coming is the project on which my friend Alex is working: Farmerline. The idea is that farmers far from urban centers could send sms or leave a message, and an extension agent equipped with a database would reply back. They are still in the design process.

So where does my placement fit in all this? No where, since I’m working under a public Farm Institute. It’s a little streched, but we’re intending on making people pay for the course I’m designing. It’s a simple of testing the idea. Would people be ready to pay 15 cedis, So less then 9$, for a 15 hour Agribusiness Training program? The answer next week.

Meanwhile, you can tell me what you think on all this.

Julien

Holy Mole!

- Sarah explaining the Sheep system

- If monkeys are not afraid of humans, it’s because they know they can easily steal cookies from our pockets.

- Cheesiest of my elephant photos

[20 days before the course prototype]

[2 days since summer midpoint]

I just arrived from the Mid-Placement Retreat (MPR), a 6-day period where all the summer volunteers and I went to the Mole National Park, in the north. The goal of all this was to take a breaktime: put on the tourist hat and snap hunt some baboons, elephants antilopes and wildbhores.

It was also about seing old faces, all with tanned skin, bony cheeks and excitement in the eyes. Something grew over the last 2 months, and I’m not talking about the beards. It was a patchwork of celebration and intense workshops, where we discussed our placements, our focus as a team, our vision as an organisation.

Talking to people made me realize that I wasn’t going in the right direction with my course. Yes, my understanding of how to teach business skills is there, but the format I initially chose is too lengthy, imprecise, unattractive. So now, I’m aiming for a format that has less content, but is more guided, and probably more effective.

The MPR also made me realize that others are doing some really good shit.

Take Guillaume and Ryan, from the Governance and Rural Infrastructure team (GaRI): they are working on Internally Generated Fund (IGR). The idea is that if people are paying for their services, as opposed of being funded by donors, the government will have more accountability to its people, and therefore the services will improve. But the system is broken: people are not convinced about giving few cents to somebody with no official papers, taxe collectors are not aware of the new fees, and the government is not using the money to pay for local services.

Or take Sarah and Naomi, from the AVC team: they are working on the lifestock market. Ghana imports more meat then it produce, yet raising goats is probably more lucrative then cultivating maize. So what is preventing a bigger market? It’s partially because people use goats here more as a fast emergency cash for their fields, or as charity for somebody in need in their family, or for gifts in funerals.

—

Should Ghana invest more in tourism?

Somehow, this question came up, during the MPR. There’s definitly an opening market for “eco-tourism” – when white people pay a lot to get lost in a forest and experience cultures. I’m not the only one asking it: just before I left, there was an article in the Daily Graphics, Ghana’s biggest newspaper.

On one side, you got people saying it will be good for the economy. Europeans and Americans are ready to pay much more for a toured visit in the jungle then the urban ghaneans, who probably don’t see the purpose. The proof is that when we went to Mole, there was only Salamingas and Afro-Americans. It can also be good for the environment: with the money, the government has interest in protecting the park from braconneers or industries, if he wants to keep the tourism in place. Wild life is preserved, deforestation is prevented.

But on the other side, you got people saying it will actually be a bad investment. Once the government improves infrastructures and access to the forests, it opens the door to multi-national tourism giants, against which the local small motels can’t compete. And then the money leaks out of the country, except for the few down-the-ladder jobs it creates. It can also lead to bad decisions. Take Mole National Park as an example: indigenous people formerly living on the territory were expelled at the inauguration time.

I guess like everything, there’s pros and cons, social costs and benefits. But there’s one reason why eco-tourism is a little turn-off for me: the message it sends to the people here. I feel there is something wrong in the image of white people chilling by the pool, going for a golf game, playing tennis, while the black people wait on tables and do the cleaning. It brings back memories from the colonial time…It’s so hard to fight the idea here that Ghaneans have to wait for white people to help them, and tourism wouldn’t help that.

I believe there’s much more benefits in investing in agriculture. If he works hard, a cocoa producer can see his farm grow, and his life condition as well. There’s must a great sense of accomplishment when he sales his first batch of dried cocoa grains. On the other side, I’m not sure there’s that much social advancement for the cleaning lady of a multi-complex resort.

And you have the right to agree, or disagree. I’d be really interested in knowing your opinions on this! 🙂

Julien